No one likes Nvidia, nuclear datacenters, and more search engine wars

8 October 2023 | Issue #10 - Mentions $GOOG, $AMZN, $NVDA, $MSFT, $META, $AAPL, $SPOT

Welcome to the tenth edition of Tech takes from the cheap seats. This will be my public journal, where I aim to write weekly on tech and consumer news and trends that I thought were interesting.

Let’s dig in.

Chips, chips, chips

A few pieces of news came out this week featuring the strategies employed at various tech companies as it relates to chips.

So far we know Google and Amazon have opted to (at least partially) use their own designed AI chips for AI workloads in their cloud computing services (TPUs, Trainium and Inferentia), leaving Microsoft as the other noteworthy member of the big three Cloud Service Providers (CSP) relying heavier on Nvidia. There have been reports in the past suggesting that Microsoft has been developing chips in secret since 2019, with some employees already having access to them. At the time, it wasn’t clear whether they would make this available to customers through Azure. According to the Information, Microsoft is planning on debuting this chip next month at its annual developer’s conference - Ignite.

Microsoft next month plans to unveil the company’s first chip designed for artificial intelligence at its annual developers’ conference, according to a person with direct knowledge. The move, a culmination of years of work, could help Microsoft lessen its reliance on Nvidia-designed AI chips, which have been in short supply as demand for them has boomed.

The Microsoft chip, similar to Nvidia GPUs, is designed for data center servers that train and run large language models, the software behind conversational AI features such as OpenAI’s ChatGPT. Microsoft’s data center servers currently use Nvidia GPUs to power cutting-edge LLMs for cloud customers, including OpenAI and Intuit, as well as for AI features in Microsoft’s productivity apps.

…

Microsoft hopes its Athena chip could be comparable to Nvidia’s H100 GPU, which has been in short supply. It isn’t clear how exactly Microsoft has compared the performance of the two chips. Several companies working on AI chips claim their hardware has more value than Nvidia’s in terms of price and performance, but AI developers largely prefer Nvidia’s because they have been using the company’s Cuda software, which speeds up applications running on GPUs.

…

When Microsoft began working more closely with OpenAI, it determined that the cost of buying GPUs to support the startup, Azure customers and its own products would be too high, said the person with direct knowledge of the decision. While it worked on Athena, Microsoft has ordered at least hundreds of thousands of GPUs from Nvidia to support OpenAI’s needs, said a person with knowledge of the matter.

For its part, OpenAI may eventually try to lessen its dependence on chips from Microsoft and Nvidia. Several job postings on OpenAI’s website indicate that the company is looking to hire people to help it evaluate and co-design AI hardware, and it has previously sought to hire someone to determine whether it should design its own AI chip, said a person with direct knowledge of the effort. Reuters on Friday reported that OpenAI executives have discussed designing an AI chip.

There are a few things happening here. CSPs at their core are selling outsourced compute in the form of GPUs, as well as data storage. In order to differentiate from each other, they need to either provide this at a lower price or provide additional value from platform as a service (PaaS) or software as a service (SaaS) (or in the case of Microsoft, make software more expensive when run on CSPs other than Azure). With the explosion in popularity of generative AI in this past year, and the CSPs effectively reselling the same Nvidia GPUs, performance hasn’t been enough to differentiate for companies building on these services. Now with Nvidia encroaching further into the CSP’s space, it is becoming more clear that chip design needs to be done in-house. For Microsoft, it makes a lot of sense (imperative, even) to control its destiny (and supply) as it relates to this part of the value chain. The company not only has a business in reselling compute but will be a heavy user of it through its co-pilot software. Controlling these costs is especially important for margins due to its fixed pricing of $30/seat/month (side note: with Google releasing its co-pilot equivalent - Duet - pricing of also $30/seat/month, while having internal TPU access, I wonder if Microsoft has already forecasted these compute savings from Athena into the pricing model).

What’s also interesting is that OpenAI, a developer of LLMs with readily available access to computing resources from Azure, is also exploring making its own AI chips.

OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, is exploring making its own artificial intelligence chips and has gone as far as evaluating a potential acquisition target, according to people familiar with the company’s plans.

The company has not yet decided to move ahead, according to recent internal discussions described to Reuters. However, since at least last year it discussed various options to solve the shortage of expensive AI chips that OpenAI relies on, according to people familiar with the matter.

These options have included building its own AI chip, working more closely with other chipmakers including Nvidia and also diversifying its suppliers beyond Nvidia (NVDA.O).

The effort to get more chips is tied to two major concerns Altman has identified: a shortage of the advanced processors that power OpenAI's software and the “eye-watering” costs associated with running the hardware necessary to power its efforts and products.

Running ChatGPT is very expensive for the company. Each query costs roughly 4 cents, according to an analysis from Bernstein analyst Stacy Rasgon. If ChatGPT queries grow to a tenth the scale of Google search, it would require roughly $48.1 billion worth of GPUs initially and about $16 billion worth of chips a year to keep operational.

This seems like a mammoth task but I can kind of see why it might want to embark on such an endeavour. There are tens of companies hot on the heels of OpenAI looking to develop a foundational LLM, of which two are from mega-cap tech companies (Meta & Alphabet) and one of those being open source. Vertically integrating is one way to gain a competitive advantage (through lowering costs). It will take years for them to develop something anywhere close to Nvidia H100s but looking at the trajectory of computing costs for the alternative - $48.1bn initially and $16bn of chips a year - the company would need to generate ~$4bn/yr in NOPAT from its existing business to generate a 15% ROIC {footnote: I assume the chips have a 5-year life}.

In other news, Reuters reported this week that Meta is planning to lay off employees in its Reality Labs division focused on creating custom silicon.

The FAST unit, which has roughly 600 employees, worked on developing custom chips to equip Meta's devices to perform unique tasks and operate more efficiently, differentiating them from others entering the nascent AR/VR market.

However, Meta has struggled to make chips that can compete with silicon produced by external providers and has turned to chipmaker Qualcomm (QCOM.O) to produce chips for its devices currently on the market.

While the company looks to be giving up on its internal chip ambitions within Reality Labs, it’s a different story as it relates to their AI chips.

A restructuring of FAST has been expected since the spring, when Meta hired a new executive to lead the unit.

A separate chip-making unit in Meta's infrastructure division focused on artificial intelligence work has likewise hit roadblocks. The executive overseeing those efforts announced her departure last week, although Meta has appointed someone else to take over her role and continue those efforts.

Meta remains committed to developing its own infrastructure and controlling this part of the value chain as it helps the company control costs and performance in this area. I’ve written in the past about the company’s product launches in this space and as a heavy user of AI compute (both now through its discovery algorithms and ad tech and the future from generativeAI powered chatbots), it makes sense for the company to control its own destiny in this part of the value chain, like many of its peers. This is a fast evolving area with lots of dynamics at play and it does make me question the durability of Nvidia’s moat. It seems like there a new pieces of information dropping every day on companies wanting to reduce their reliance on the company, which makes it tougher for investors to bet on its terminal value. The near term set up will continue to look great for the company until supply better matches demand but I can’t help but wonder what the demand environment will look like five or even three years out. It would be less of an issue if the company traded at 20x earnings but it’s 31x with arguably peak margins. I have no dog in this fight but would be interested to hear the bull argument (that isn’t just going to point me to momentum/N12M order book).

Can’t get enough datacenters

Speaking of things in high demand and short supply, a couple of articles caught my attention this week regarding datacenters. This piece by the FT reports on how the growth of bits is impacting the physical world.

Every email sent, photo or video captured, crypto token traded and online article published adds to the growing mass of digital data worldwide.

Last year alone, nearly 100tn gigabytes of data were created and consumed, according to market researcher International Data Group, equivalent to 4.5tn times the entire text contents of Wikipedia. And the figure will nearly double again by 2025.

Powering this growth are the energy-intensive data centres around the world that process, host and store digital information but which are fast becoming insufficient in capacity.

Developers are scrambling to expand existing centres or to build new ones in order to meet demand. An ever-growing number of people and devices are connecting online; streaming services such as Netflix and Spotify have millions of concurrent users; and the advent of cryptocurrencies and their processing-heavy mining methods have all added to the strain. Bitcoin mining and trading consumed almost triple the electricity of the entire island of Ireland last year, the Cambridge Centre for Alternative Finance estimates.

Generative AI is accelerating this need for more data centers as LLMs usage of computing power is growing exponentially.

Large language models such as GPT-4, which powers ChatGPT, require vast amounts of computing power to create and improve. While OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT, doesn’t publish exact figures, its older model, GPT-3, is estimated to have cost between $3.2mn and $4.6mn in processing power to train. For the training of GPT-4, that cost had jumped to over $100mn, according to an estimate by Sam Altman, OpenAI’s CEO.

Meanwhile, the amount of electricity that data centers consume is also raising questions about their sustainability.

A personal computer contains a hard drive for storing data, a processor capable of modifying that data, networking hardware to connect to the internet and a battery or a power supply to provide the energy for it all. As the electricity passes through your laptop’s hardware, it produces heat which is cooled by a fan.

Data centres take these core concepts of a standard computer and scale them to an enormous level. Instead of one hard drive on your computer for storing photos and home videos, a data centre will contain multiple thousands of hard drives and powerful processors inside “servers” which store, process and host vast quantities of data, for example the entire video catalogue of YouTube.

Vast arrays of servers are stored in rows of energy-intensive “racks” that produce incredible amounts of heat. This heat requires specialised cooling systems to regulate. A data centre needs to be kept between 18 to 27 degrees Celsius in order to stop the hardware deteriorating.

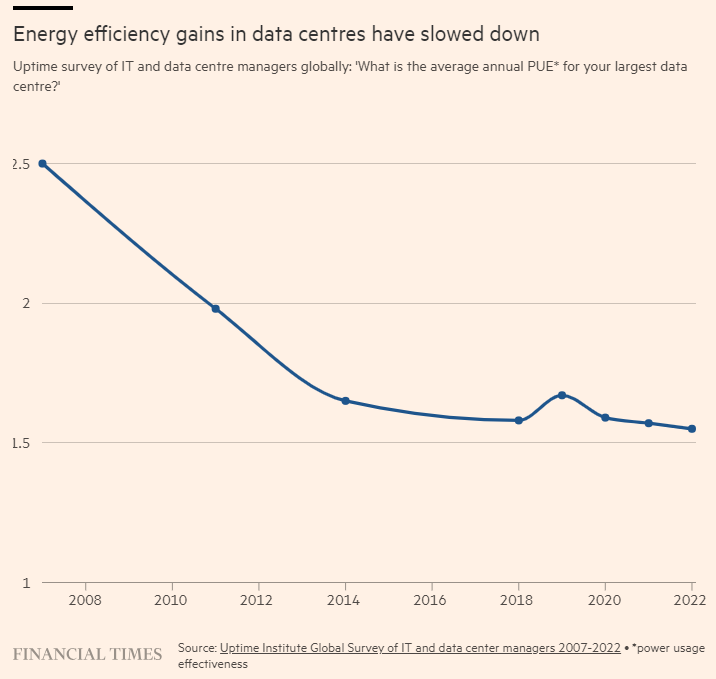

Energy efficiency gains also seem to have plateaued.

In comes nuclear energy: Cloud Providers Eye Nuclear Power as AI Saps Data Centers.

As cloud providers struggle to cope with fast-growing demand for artificial intelligence computing, they may turn to a source of power that has gone largely untapped by the cloud industry: nuclear.

What might be the first data center site with direct access to a nuclear power plant, located outside Berwick, Pa., is now on the auction block. The sale has drawn attention from cloud providers that are running out of power from the existing grid and see nuclear energy as a potentially cheaper and carbon-free way to power data centers versus fossil fuels. Unlike solar and wind power, which fluctuate depending on the weather, nuclear power is a more stable source of clean energy.

Investment bank DH Capital, which is leading the sale efforts for the data center site, told at least one potential bidder that the seller wanted between $700 million and $1.4 billion for the 1,200-acre space, based on the total energy capacity the site would have if additional data center facilities were built on it. While it’s difficult to compare the nuclear-powered site to other data center projects, that price is on par with what large companies such as Apple and Meta Platforms have spent developing data centers, according to data from real estate publication Dgtl Infra.

The Talen nuclear site could provide access to between 475 and 950 megawatts of power across several data centers. To put that into context, the campus could hold more than a quarter of the power that comes from Nova, the largest data center hub in the U.S, located in Northern Virginia, according to a person who works in the industry.

Amazon Web Services, Google, Microsoft and other cloud providers have been seeking more space for servers to power AI. But finding real estate with ample access to power in the U.S. has been particularly challenging for the companies.

AI software requires more energy than traditional computing because much of it uses power-hungry processors known as graphics processing units, which Nvidia makes. Many existing data centers cannot draw enough power for Nvidia’s most advanced GPU chips, known as H100s, which has sent cloud providers scrambling to find new locations for AI data centers.

Cloud providers’ interest in nuclear power has picked up in recent months, most notably from Microsoft.

“Power is probably the biggest [factor]” influencing cloud providers’ data center choices, Fitzgerland said.

The price of Uranium recently reached $73, the highest since reaching that level before the Fukushima disaster in 2011. It’s not just CSP demand driving this and there are other factors at play, but i’m not Uranium or commodities expert so I won’t comment further. Just thought it was interesting to note.

Source: Trading Economics

More search engine wars

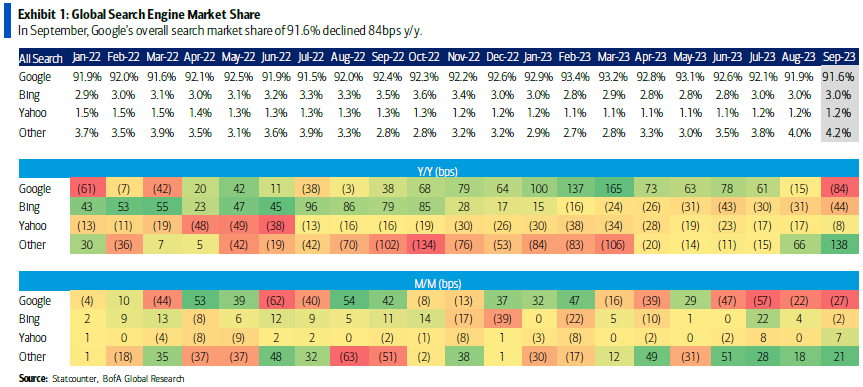

Following on from last week’s post on search engine wars, this week came out with some more tidbits on the business of search.

The whole article is worth a read but Satya’s testimony in Google’s antitrust trial shed some insights on how Microsoft views the market.

Severt’s questions focused for a long time on Google’s billion-dollar deal to be the exclusive search provider on Apple devices and what it might mean to Microsoft if it were to have that deal instead. “It would be a game-changer,” Nadella said. He said that Microsoft was prepared to give Apple all of the economic upside of the deal if Apple were to switch to Bing — and said he was prepared to lose up to $15 billion a year in the process. Nadella even said he was willing to hide the Bing brand in Apple users’ search engines and respect any of the company’s privacy wishes, so urgent was his need to get more data at any cost. “Defaults are the only thing that matter,” he said, “in terms of changing user behavior.” He called the idea that it’s easy to switch “bogus.”

For Nadella, becoming Apple’s default search engine wouldn’t be about the money, at least not directly. “We needed to be less greedy and more competitive,” he explained. A sudden increase in distribution, he said, would give Bing an increase in what Nadella called “query flow,” which essentially just means more people would do more searches. More incoming searches means more data the Bing team can use to improve the search engine and more reasons for advertisers to come to the platform. An improved search engine gets used more, which means more data, and round and round it goes. This is the virtuous cycle of search engines, and Nadella believes Bing could use that cycle to quickly catch up to Google’s quality. Or, if you’re Bing — the losing party that can’t get the queries, the data, the advertisers, or the users — “it’s a vicious cycle.”

Has Microsoft tried to become Apple’s default search engine, Severt asked? Yes, Nadella said. How’d it go? “Not well,” Nadella deadpanned. Not only are the economics of the Google deal hugely favorable for Apple, he said, but Apple may also be afraid of what Google would do if it lost default status. Google has a number of hugely popular services, like Gmail and YouTube — what if Google used those apps to relentlessly promote downloading Chrome, thus teaching people to circumvent the Safari browser entirely? That fear, Nadella claims, keeps Apple and Google together as much as anything.

Both Severt and Mehta asked Nadella about how AI — and specifically Microsoft’s massive partnership with OpenAI, which has completely changed the way Bing works — will change the search market. Severt even specifically referenced Nadella’s comment about “making Google dance,” which Nadella said to The Verge earlier this year. Nadella walked that one back a bit: “Call it the exuberance of someone who has 3 percent share,” he said.

The fact that Microsoft were (are?) willing to lose up to $15bn a year with additional concessions to become the default search engine for iPhones says a lot about how lucrative the existing partnership is for Google and Apple. Despite all the noise about embedding generative AI into Bing and ‘making Google dance’ at the beginning of the year, search engine market share has barely changed.

It’s kind of funny seeing a $2.5trn company CEO paint the picture of its $1.8trn market cap competitor as a Goliath cornering the market even though it generates 18% more (~$13.5bn) in operating income. It also shows how risk averse they are, only willing to lose that sum for a partnership because they see default status as a proven path, rather than spending money on improving the product or marketing it over the years. Bing isn’t exactly struggling as a product - it generates $12bn a year in revenue. It’s just convenient for the Microsoft CEO to attribute a lack of success with Bing to this partnership rather than internal strategic decisions. iPhones aren’t the only phone ecosystem for Bing to collect search data from. It could’ve tried to outbid Google on Samsung devices too. I’m interpreting some of these comments as theatrics more than anything else.

Spotify audiobooks and Supremium plans

From Variety

Spotify is hoping to jump-start its push into audiobooks — announcing that paying subscribers can access up to 15 hours free listening per month from among 150,000 titles.

A year ago, the audio streamer announced that users would be able to purchase and listen to 300,000 audiobooks on Spotify. Spotify’s entry into the audiobook market came after closing its acquisition for audiobook distributor Findaway in June 2022, paying about $119 million in cash for the company.

About half of that catalog will be available as part of Spotify Premium subscriptions. Initially, the company is offering all Premium individual accounts, as well as plan managers for Family and Duo accounts, 15 hours of listening per month. The feature will be available for Premium users in the U.K. and Australia starting tomorrow, with the U.S. following later this year.

This new deal lowers the bar for adoption but will be potentially gross margin dilutive if the company doesn’t convert users into regular listeners. We don’t know what deal it has worked out with publishers but assuming Spotify needs to pay the publishers per stream, it won’t receive additional revenue from subscribers unless they purchase hours beyond the free 15. For voracious listeners, Audible seems like a better deal at $8 a month for unlimited consumption. Spotify is probably hoping that they capture listeners that wouldn’t have signed up for Audible in the first place - expanding the TAM via convenience like they did with music streaming.

From TechCrunch

It looks like Spotify’s rumored “Superpremium” offering is gearing up for a launch. According to references discovered in the Spotify app’s code by Chris Messina, the Superpremium service now has a flashy logo and a longer list of features beyond the 24-bit lossless audio we’ve been anticipating. In fact, the broader feature set appears to be set to include the recently discovered AI playlist generation tools, advanced mixing tools, additional hours of audiobook listening and a personalized offering called “Your Sound Capsule.”

Messina had also uncovered Spotify’s development of AI playlists earlier this week, which would allow users to create unique playlists using prompts. Spotify declined to confirm the development at the time, noting it wouldn’t comment on possible new features

This plan comes in at almost double the single Premium plan ($10.99) and is targeted at the true audiophiles. It’s an interesting test case but should be meaningfully accretive for the company. We will see what level of adoption this gets. It should be noted that when asked for comment, the company stated it they don’t have anything new to share.

That’s all for this week. If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, consider subscribing or sharing with a friend

Share Tech takes from the cheap seats

I welcome any thoughts or feedback, feel free to shoot me an email at portseacapital@gmail.com. None of this is investment advice, do your own due diligence.

Tickers: GOOG 0.00%↑, AMZN 0.00%↑, NVDA 0.00%↑, MSFT 0.00%↑, META 0.00%↑, AAPL 0.00%↑, SPOT 0.00%↑

I guess the bull case for Nvidia is just that margins might be peak, but sales aren’t. Not even in a future with more competition, simply because this market is going to be vastly bigger than it is now. (Not necessarily endorsing this myself)