Shein's IPO, Apple squeezing suppliers, and more LLM/AI

3 December 2023 | Issue #17 - Mentions $HM.B, $ITX, $META, $GOOG, $AAPL, $MSFT, $AMZN

Welcome to the seventeenth edition of Tech takes from the cheap seats. This will be my public journal, where I aim to write weekly on tech and consumer news and trends that I thought were interesting.

Let’s dig in.

Shein files for a US IPO

Fashion company Shein has confidentially filed to go public in the United States, according to two sources familiar with the matter, in what is likely to be one of the most valuable China-founded companies to list in New York.

Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase and Morgan Stanley have been hired as lead underwriters on the initial public offering (IPO), and Singapore-based Shein could launch its new share sale in 2024, the sources said.

Shein has not determined the size of the deal or the valuation at IPO, the sources said. Bloomberg reported earlier this month it targeted up to $90 billion in the float.

The company founded in mainland China in 2012 was valued at more than $60 billion in a May fundraising, down by a third from a funding round last year.

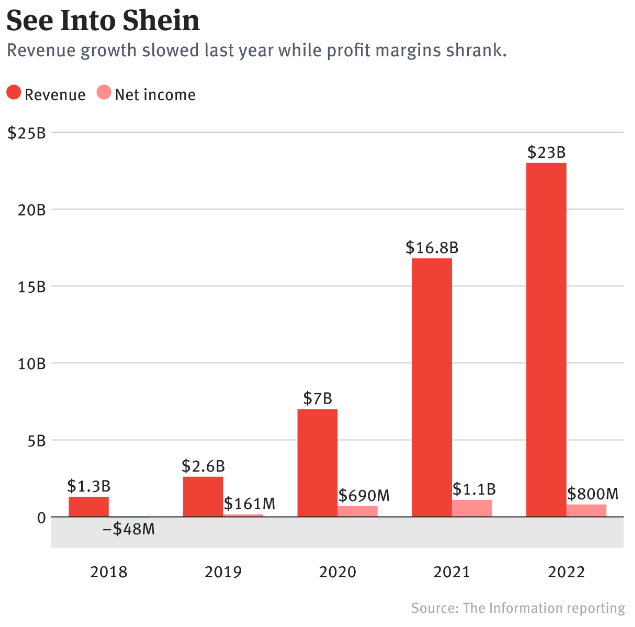

Shein grew revenue by 37% in 2022 according this profile from The Information, which would put the $66 billion valuation at around 2x LTM sales or ~60x LTM earnings assuming it maintains the same margins and hits its 2023 sales target. When compared to other fast fashion peers such as Hennes & Mauritz (45x LTM P/E, 6% revenue growth) and Zara-owner Inditex (25x LTM P/E, 10% revenue growth), it actually looks quite reasonable, assuming revenue doesn’t decelerate into the teens.

The difference with Shein though, is that its goal is to become much more than just a fast fashion ecommerce retailer. The company was founded in Nanjing, China in 2008 by US-born entrepreneur and search engine specialist Chris Xu as a low-cost, online apparel merchant. It became popular with women in their teens and 20s for having low priced clothes that shipped to more than 150 countries and regions worldwide and went viral using social media. It acts as an online marketplace that brings together thousands of clothing factories in China under Shein’s label and uses software to collect data about which items are popular or not to know what to promote. Items are produced in small numbers, between 100-200 pieces a day, before it becomes popular and is then mass-produced once they’ve gained traction. Last year, 60,000 new styles and sizes of apparel were added monthly. Orders are shipped directly from these factories, which allows individuals of most countries to avoid paying import tariffs, keeping prices low.

As the company has scaled up, it has begun to branch out from its roots to tap new sources of growth.

From The Information

The company plans to offer faster shipping and a broader range of merchandise, putting it in more direct competition with Amazon. But one year in, the payoff from that strategy has been mixed: Shein has managed to make progress in newer markets like Brazil, but it still faces an uphill battle in the U.S. and Europe, its biggest regions in terms of sales.

To accelerate growth, one of Shein’s new priorities is recruiting outside sellers in markets including Brazil and the U.S. Shein has already made a push to become a big seller of items like beauty products and household goods—nonapparel items made up around a third of its sales volume over the past two years, according to Shein’s financial information reviewed by The Information. But bringing in outside sellers could help Shein list more products in other categories faster than if Shein makes those items itself.

Shein has also been building out manufacturing and warehousing capabilities closer to its customers in the U.S., Europe and Latin America in order to offer faster delivery times, a move that could also insulate the company from volatility in the cost of air freight from China. Those costs surged during the pandemic and added to the company’s logistics and fulfillment expenses, causing Shein’s net profit margins to fall in 2021 and 2022. Local manufacturing would also protect Shein from changes to tariff policies that would make direct shipments from China more costly.

The final part of the strategy is selling items that are more expensive than the $3 crop tops Shein is known for. Shein has started offering more premium clothing lines of its own, and this year it inked partnerships to bring Forever 21 and U.K. women’s brand Missguided onto its sites.

Shein told investors last year that all of these new efforts combined could bring in nearly $5 billion in additional revenue by 2025, which on top of growth in its existing business would take total revenue to $58.5 billion, versus the $23 billion in sales it generated last year.

….

In the future, Shein is planning to start offering its own warehouse space and fulfillment services to outside merchants in the U.S., a person close to the company said, a strategy that seems to rip a page straight from Amazon’s playbook.

Shein opened a 659,000-square-foot distribution center in Whitestown, Ind., in 2022 that it has been using to store popular Shein items before shipping them to shoppers. It has steadily expanded that facility over the past year, more than doubling the size to 1.8 million square feet, a Shein spokesperson confirmed.

It’s going to be interesting to watch how this plays out. The playbook Shein is running is not too dissimilar to how other popular ecommerce marketplaces scaled up. Amazon started with books and branched out to other categories while Sea-owned Shopee was also popular with fashion and beauty products and branched out over time. Shein faces an uphill battle in the US though, up against a large incumbent that’s built up over two decades of logistics infrastructure. That’s not to say it’s impossible. Fast fashion was a fairly mature market before Shein entered but it managed to gain a large slice of the pie by executing the unique sales proposition of low-priced, data-driven goods. I also wouldn’t be surprised if it introduced ads over the next couple of years as more merchants join the platform, following the ecommerce rite of passage. I know one thing is certain - with a potential IPO on the horizon comes extra funding that will be spent on growth. Google and Meta look to be continued beneficiaries from increased competition in ecommerce.

Related: Shein and Amazon Are Both Good for the Ad Business

Bargaining power of buyers

Being a supplier to Apple can be a lucrative opportunity. The company generates $383 billion in revenue a year and allocates $214 billion towards its suppliers for the production of its goods. However, this opportunity can also have its drawbacks. As the world’s largest smartphone maker, Apple holds considerable sway in the industry. An insightful profile on Apple's procurement executive, Tony Blevins, published by The Wall Street Journal a few years ago, unveils the company's assertive tactics employed in its supplier relationships.

For the iPhone, Mr. Blevins worked with Apple’s contract manufacturers and managed the purchase of parts such as modem chips. Sales of the phone soared after its 2007 introduction, forcing suppliers to scramble to meet volume. Mr. Blevins played one against another for better terms.

When STMicroelectronics NV in 2013 refused a request to lower prices for gyroscope sensors—parts that help the phone screen adjust to movement—Mr. Blevins threatened to find an alternative, according to a former STMicroelectronics executive.

The supplier held its ground, only to watch the business shift to a rival. That killed an estimated $150 million in the supplier’s annual revenue, according to data from IHS Markit, amounting to a fifth of its sensor sales.

STMicroelectronics didn’t respond to requests for comment. It continues to supply components for Apple products.

Mr. Blevins rotated staff members every few years to keep them from developing supplier relationships that might dilute their focus on saving Apple money, former employees said.

…

Mr. Blevins enforces Apple’s nondisclosure agreements, which can carry potential penalties of $50 million or more.

In 2017, Japan Display Inc. held a news conference and disclosed it had received orders for its latest liquid crystal displays. It wanted investors to know this because some phone makers were dropping LCD in favor of new display technology.

Apple was among the smartphone makers that had expressed interest in a purchase, The Wall Street Journal confirmed at the time. Mr. Blevins called a top Japan Display executive and accused him of violating Apple’s nondisclosure agreement. “Are you stupid?” he said, according to a person familiar with the call.

Apple later demanded that Japan Display pay $5 million for breaching its contract, according to this person. Although Japan Display didn’t pay the penalty, it agreed to submit future news-conference materials to Apple before events, another person close to Japan Display said. Apple’s contract gave it the right to review the supplier’s emails and executives’ calendars.

A Japan Display executive described Apple’s nondisclosure agreements as “torturous,” saying he had never heard of others demanding so much.

More recently, The Information wrote a piece on Apple’s lopsided arrangement with recent IPO-Arm holdings, the British chip designer whose IP supports much of the semiconductor industry.

In 2017, SoftBank CEO Masayoshi Son gathered a group of executives from Arm Holdings, the British chip designer SoftBank had just bought, to complain about one of its most important customers: Apple.

In a conference room in Tokyo, Son told the group that Apple paid more for the piece of plastic that protects the screens of new iPhones than it did to license Arm’s intellectual property, according to a person with direct knowledge of the meeting. To punctuate his point, Son pretended to peel the plastic wrap off an iPhone in front of the group.

Six years later, Arm still faces the same problem: Apple pays less than 30 cents per device for the right to use Arm-based chips in the hundreds of millions of iPhones, iPads, Macs and Apple Watches it sells each year, according to people with direct knowledge of the matter. That’s the lowest royalty rate among Arm’s smartphone chip customers, traditionally its biggest group of customers by revenue, the people said. As a result, Apple accounts for less than 5% of Arm’s sales, around half the figure for each of the chip company’s top two customers, Qualcomm and Mediatek, they said.

The entire article is worth a read, but it further highlights the doubled-edge sword that comes with being an Apple supplier. Even though Arm’s relationship with Apple has opened up doors for the company to win business from other companies, I wouldn’t have guessed that such a critical piece of IP is only yielding 30 cents per device. It may have to do with the fact that Apple only licenses Arm’s architecture and designs its own cores tailored to its specific needs rather than licensing Arm’s off-the-shelf design that its other customers use. Apple was also an early customer that persuaded Arm to accept a low flat royalty fee per chip regardless of how many Arm cores it used, instead of being based on a percentage of the price of the chip. Around the same time as Arm’s IPO, the two companies signed a new licensing agreement that extends beyond 2040, [footnote: Apple was also among a group of 10 cornerstone investors that bought a combined $735 million of shares in the offering] so it’s unlikely that Arm will have much luck trying to squeeze more out of the relationship.

More LLM commentary

There were a couple of good pieces of AI content this week: The Ultimate AI Roundtable on 20VC and Hugging Face CEO on What Comes After Transformers from The Information

Interesting snippets below:

From 20VC

On commoditisation of the foundational model layer

“I certainly think we will. And this may not be a popular position. Obviously, OpenAI is charging ahead, sort of leading the way right now. I think the market forces at work mean there's just immense energy to have an open source equivalent. Meta appears to be highly motivated to open source its work. Many folks want to run these themselves and tune them themselves and so on. That is hard and expensive today. But I can't think of another thing in time and history where something hard and expensive in tech has lasted all that long. It's going to be commoditized.” - Jeff Seibert, Founder & CEO of Digits

Open vs closed

“It's very simple. It's because no outfit as powerful as they may be has a monopoly on good ideas. If you do it in the open, you recruit the entire world's intelligence to contribute to things and having ideas and ideas that you may not have thought about, which an outfit with 400 people has no chance thinking about, or even a large company with 50,000 employees may not want to devote any resources to, because they may not think its so useful in the long term or they have more urgent things to take care of. So you give it away and then you have tons and tons of people, some of whom are undergraduate students or people in their parents' basement. So coming up with amazing ideas that you would never have thought about or willing to spend the time to crunch down the 7 billion weight Llama so that it runs on a Mac on a laptop. I think that's why open source projects succeed, particularly when they concern basic infrastructure.” - Yann LeCun, VP & Chief AI Scientist at Meta

“So I'm a big fan of open source, right? I would like it to be true that with open source, we could just keep up with all of that. But I think that's just incredibly naive. OpenAI has this very deep understanding of how people want to use language models. Basically, nobody else has. And they have this giant economy of scale where they can serve up language models very cheaply because they get so many requests coming in at the same time.” - Douwe Kiela, CEO of Contextual AI

“I mean, certainly you can't deny that OpenAI is ahead by a lot. I predicted that we'll have a GPT4 equivalent model before the end of the year that's open source. Of course, GPT4 keeps getting better and better so my prediction was for the version we had like a few months ago. But I actually think that with models like Llama 2 from Facebook and everyone there, I do think open source will take over a lot of use cases, right? It's already getting close to GPT3.5 when there's this much excitement in so many careers depending on understanding these models. Imagine all the researchers in all these universities, right? They're all the sudden kind of out of a job unless they have an LLM that works really, really well and they can do useful things with it. Then I've gone and just say, Oh, let's just from now on run our entire research agenda on some closed API that we cannot analyze and understand and improve and publish papers on. So they need to have a model to exist. And those are all very, very smart people now that don't have as many resources usually, they can’t train a single model for like 20 or 50 million dollars, because they're in universities, but they're finding ways, they're collaborating and they're probably going to work on foundational models that are fully open source. And we now see this with like surprisingly Facebook being at the very forefront of it. People will layer on top of that, make it better. And then there will be open source versions you can run on your phone and those will get better and better over time. And so I'm quite bullish on the LLMs in particular, getting more and more commoditized. And yes, there will be a few foundational companies, you know, just here in Anthropic also behind OpenAI working very hard to catch up with them. And they did raise a lot of money too. And it's good to have some competition in that space. But my hunch is a lot of people will be okay with an open source model too.” - Richard Socher, CEO You.com

Does value accrue to application layer or infrastructure layer?

“I ran this analysis. So in web2, if you take the top three clouds and you look at their market cap, so AWS, GCP, and Azure, it’s about a $2.1 trillion market cap just for the cloud businesses. And then if you take the top 100 publicly traded cloud companies, both on B2C and B2B side so Netflix and ServiceNow, they have equivalent market cap about 2.1 trillion for both. So ones at the infrastructure layer, ones at the application layer, market cap is basically equivalent. The difference is the infrastructure layer, there are three businesses and at the application layer, there are 100. If the analogy holds, as an investor, your odds of success are going to be significantly higher at the application layer because the diversity of needs there is greater.” - Tom Tunguz, GP at Theory Ventures

New pricing models with AI

“If AI is to be the force that it can be, I think you will get a new architecture, a new business model emerging from it versus what we only see right now, which is kind of a sustaining architecture, which is just that of a co-pilot, which fits on top. What is the new architecture and what is the new business model? I think the way to encapsulate would be this idea of selling the work, not the software, and that we’ll move from a paradigm where you might think of it as moving from what we see right now as a co-pilot and moving to what I think about as a control center, where we'll sell an SLA on work, not an SLA on uptime. And so we'll move from a world where we all as users of software kind of are like monkeys doing data entry usually. Like what's most software? It's a database with a form on top of it for users to manage information, put information, get information out.

And so we'll move from a world where the users are doing all this work to a world where the application is doing a lot more of the work, right? Where the AI, the notion of agents inside of it, etc. is doing it. And where right now like you go to any SLA for any software, you get uptime, you get support SLAs for questions and things like that. I think there's a world where we move to in the future where like an SLA, maybe almost looks more like a BPO would in some sense. An SLA will be you wanted a efficiency of X on your market, we delivered that. You wanted this many leads from an SDR team, like we do that. You wanted this sort of accounting and books closed by two days at the end of a quarter. We'll give you an SLA on that, not on the software's up. You'll go from copilot to control center it'll be a UX for a worker, which is dominant to UX for managers. You'll go from a seat add on to software and labor, and you'll go from SLA on like reliability to SLA on outcomes on work performance. That's what can be offered up by this. You see very little of it so far. I think AI is offering the potential for that architecture shift. If we get that, the whole seat model, the whole the worker does it, and the product paradigm, the distribution in terms of who you can reach changes because ACVs change. In that way, I think it will be very different to mobile, which was mostly another UX, but the same architecture, same business models.” - Miles Grimshaw, GP at Benchmark

“I think a lot of work is going to get handed over to LLM's over the next five years. We'll got to start trying to like price against the work that's being done, not price against the seats or the employees, but just say, how much is it worth for you to have all of your digital assets created dynamically? Or how much is it worth for you to have like your customers get sub second replies to common questions? Like that's the actual right way to think about pricing in the future.” - Des Traynor, Co-founder of Intercom

From The Information

I’ve previously referred to the practice as ‘cloud pyramid schemes’ but perhaps Clem Delangue’s reference to it as ‘cloud money-laundering’ makes more sense.

Unlike the rest of the tech industry, AI this year has looked like a page from the go-go days of 2021, in terms of capital investments. But a lot of it has been driven by cloud providers such as Microsoft, Google and Amazon (plus Nvidia), which aren’t doing it out of the goodness of their hearts. A large chunk of those dollars return to the cloud providers in the form of contracted cloud spending, which Delangue jokingly calls “cloud money-laundering”—a charge the cloud providers strenuously deny.

Semantics aside, Delangue argues that because these cloud providers make more money if customers develop and use larger models that need more computing, they have an incentive to sell such models even if smaller, specialized ones make more sense for customers.

He also seems to think that open-source models will close the gap with closed-source LLMs, though he’s been saying it for a while and his company will benefit if it happens.

What comes after transformers?

Today’s most popular LLMs, like GPT-4 and Llama 2, are based on transformer architectures, which essentially predict the most-likely next word in a phrase. Those models have been criticized for being prediction machines rather than reasoning through problems. That’s led many to wonder what might be coming next. Delangue is especially excited about reinforcement learning, a well-known machine learning technique that trains AI models by rewarding them for making certain decisions. Facebook used the technique to boost engagement, for instance, and Wayve AI uses it to power its self-driving car prototypes in London.

Delangue also is looking forward to breakthroughs in video generation beyond what we’ve seen from startups like Pika and Runway, and in domains like biology and chemistry. Additionally, Delangue believes there will be lots of interesting research with time-series models, which predict the most likely next event based on the previous series of events. Developers could combine time-series models with text-based LLMs to create AI models that are much better at predicting and preventing fraud, for instance, Delangue said. Recent breakthroughs from OpenAI could hint at what’s coming next: The company’s secretive Q* model has been able to solve math problems it hasn’t seen before, and OpenAI researchers have experimented with a machine learning concept known as “test-time computation,” which is meant to boost language models’ problem-solving abilities.

AWS:reInvent

I recommend reading the pieces from Stratechery on Amazon’s cloud event here and here.

I’ll mention a couple things that stuck out to me though.

First, Amazon’s announcement of its own co-pilot Q further reinforced the view of co-pilots being an incumbent business model rather than a disruptive innovation. Like what Miles Grimshaw said in the podcast from above, for AI to truly be an impactful technology, the business model surrounding it needs to be completely re-written. What’s currently available in the application layer are sustaining innovations that make existing workflows more efficient. Incumbents are disincentivized to introduce these new models because it could potentially upend their lucrative recurring revenue seat-based models. The space is quickly evolving but it’s possible that the leaders in the application layer will look very different 5 years from now as generative AI continues to get developed.

Secondly, following the tumultuous week that transpired at OpenAI, it has created an opportunity for AWS and GCP to attract additional AI investments as businesses seek to diversify their exposure to Large Language Models (LLMs). During that eventful weekend, it became evident that some OpenAI customers contemplated switching to alternatives like Anthropic, Microsoft and Google. In Ben's article, he highlights how AWS CEO Adam Selipsky promptly underscored the importance of having a wide array of model providers to choose from.

“We have been saying since we started laying out our generative AI strategy, almost a year ago, how important it is for customers to have choice. Customers need multiple models – there is no one model and no one model provider to rule them all. The events of the last few days have shown the validity and the usefulness behind the strategy that AWS has chosen. Customers need models they can depend on. Customers need model providers that are going to be dependable business partners. And customers need cloud providers who offer choice and offer the technology that enables choice. Those cloud providers need to want to offer choice as opposed to being driven to provide choice. The importance of these attributes, which AWS has been talking about and acting on for more than 17 years, has become abundantly clear to customers in relation to generative AI.”

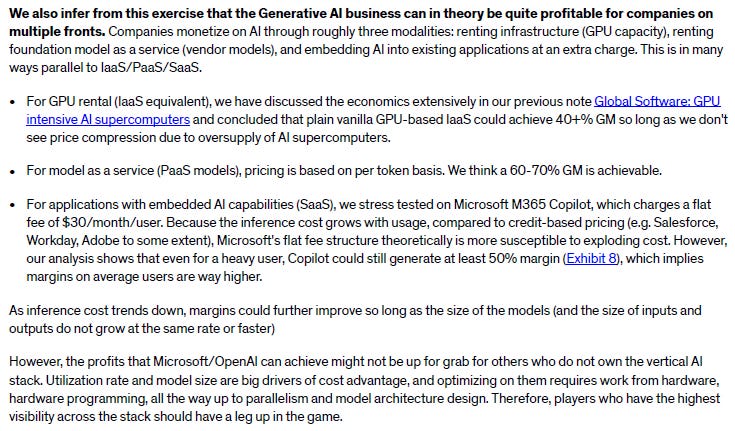

Microsoft seems to also be cognisant of this need as I’ve wrote about last week when it announced Models as a Service. At least on Bernstein’s estimates, this looks to be the most profitable part of the stack.

That’s all for this week. If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, consider subscribing or sharing with a friend

Share Tech takes from the cheap seats

I welcome any thoughts or feedback, feel free to shoot me an email at portseacapital@gmail.com. None of this is investment advice, do your own due diligence.

Tickers: $HM.B, $ITX, META 0.00%↑ , GOOG 0.00%↑ , AAP 0.00%↑, MSFT 0.00%↑ , AMZN 0.00%↑

Excellent 🤘🏼