GenAI and Software TAMs, misalignment of investment horizons

20 August 2023 | Issue #6 - Mentions $MSFT, $CRM, $NOW, $ABNB, $GOOG, $SE, $ADYEN, $BABA, $PYPL

Welcome to the sixth edition of Tech takes from the cheap seats. This will be my public journal, where I aim to write weekly on tech and consumer news and trends that I thought were interesting.

Apologies in advance for the extra-long post this week. I will be taking next week off and wanted to share some thoughts I’ve been contemplating before I do.

Let’s dig in.

GenAI, software TAMs and the future of customer service support

A key debate that’s been going on in software recently has been: what happens to the TAM for software companies when there’s mass adoption of GenAI?

Dave argues in his twitter thread that as AI gains adoption across the enterprise, staffing (he uses a call center as an example) is reduced because of automation and efficiency, so therefore the quantity in the price*quantity = market equation is reduced dramatically, lowering the overall TAM for call center software companies.

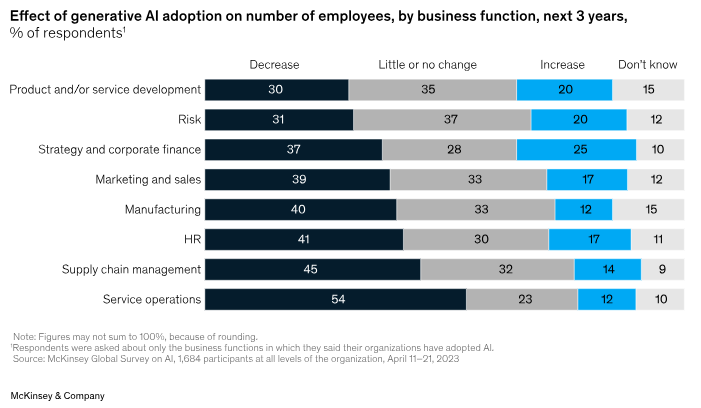

It’s still very early in the adoption cycle but this survey result from McKinsey seems to suggest this will be the case at least within service operations.

Investors have rightly been asking management teams how they’re thinking about price and quantity when determining the economics of their product set. Some software companies (MSFT, CRM) have led the industry in giving us a preview of what it’ll potentially look like. I thought this excerpt from CJ Desai, President and COO at ServiceNow’s Investor Day was good.

“So, you will ask me, okay, CJ, that's all great, strategy sounds great, what does this mean for monetization, okay? I would say, first of all, I'm going to address this very specifically because some of you asked this question on our earnings call. Number one, the value that gets delivered to our customers is higher on the right side, which is domain specific versus general purpose LLM, okay? So, the value our customers get through Gen AI will be higher on the right side. It will be there on the left side as well, but right side is higher, okay? So, that's number one.

We can capture this value and we are going to price for it. We are 100% going to price for it. So, you'll say, okay, CJ, how are you going to price for it. And when we launch ITSM Pro, that was the number one question asked. For the folks who were here on 2019 Investor Day, I know many of you were, and they said, wow, what about seat compression. Wow, seat compression, ITSM, what's going to happen. So, seat compression and what's going to happen? And you look at our ITSM results, not only customers because they got value, they have continued to expand ITSM Pro, but they've also expanded our seats on ITSM Pro and we have four years of history with that. We have the same conviction here that the value we deliver we will be able to price for it and that price could be it's P times Q, right? So you can either have a higher price via add-on SKU, with some kind of meters around AI that, okay, you use this many API calls, this is how much you pay. So you have an add-on for something like an ITSM Pro.

But as we enable more ServiceNow developers through our Creator Workflow, it can be Q as in quantity and we can have higher level of quantity of our products sold because now we will have more developers who are using App Engine to create Gen AI as a text-to-X, text-to-code, text-to-workflow, text-to-app someday. That's our conviction that it is P times Q and you can charge higher pricing on some meter. It's most likely going to be the API calls. And if we can show accuracy, which we are seeing today on the right side, we know that.”

These prices ($30/month/user at MSFT and $360k annually at CRM) may seem high at first glance but I suspect as more data is collected on usage of GenAI API calls it will allow companies to adjust them down the line1.

I enjoyed this podcast from Invest Like the Best on Software and AI which gave some insight to a lot of the questions investors have been thinking about. Des Traynor is the Co-founder and Chief Strategy Officer of Intercom, a customer service software provider. The whole podcast is worth multiple listens, but I’ll share some interesting snippets.

What results they saw when they added GenAI capabilities to their customer service bot, Fin

In terms of like the complexity, the nuance, customers will send us seven questions, not knowing they're talking to a bot. Seven questions with nested if this, then how do I that. Fin just blitzes through genuine conversations that might have taken a support rep an hour to aggregate all the information.

Fin is just blitzing it, and there are some shocking stats. We've seen customers see 50% of their support volume drop. We've seen, on average, most customers who turn Fin on would know what would work, literally clicking an on button are getting 15%, 20%, 25% of their support volume just going away, straightaway.

What the future of customer support looks like and how much human involvement there’ll be

“I think we're somewhere in the middle where whole workflows are removed in Intercom's case, but not the entire platform. There are still humans doing support, and they still need a pretty rich and powerful support help desk and they still need a messenger to communicate through. All of that needs to be available through APIs. You still need a knowledge base. There's a lot of other stuff that still has to be built. And then obviously, Intercom also has proactive support sort of the messaging pieces as well.

So I think what we have had to do is reimagine and throw away parts of Intercom that assumed, say, our reporting infrastructure is very different in a world where 50% of the responses are going through AI. All of a sudden, people care a lot about the AI reporting whereas they didn't before. Measures like first response time right now are no longer really valid because you have this tracked AI and all that stuff.

So I think if you can imagine of all the support work that happens, X percent of it's gone, the remainder still needs, what we would call, like a classical high-quality help desk. A good chunk of the work just disappears entirely. And then there are some features or some workflows, we'll see how we play it out where we'll probably heavily augment them with AI. So you could imagine analyzing what are the most common complaints from customers today.

I can imagine we'll throw a lot more AI at that feature to remove the needle in a haystack approach and actually maybe the new version of that report has just a summary paragraph that tells you here is the biggest issues going on today. So I think that will be an example of workflow displacement.

But I think in general, we believe the future of customer service will still involve humans and bots. And we care a lot about making sure that they can work together really well and they can interoperate, and we have this idea of a flywheel where the humans help the bots and the bots help the humans. If we're right, anyone who wants to be this also needs to have a pretty high-quality help desk, too.”

“Where we want them to spend their time is on high-value brand building, high urgency, high-impact conversations. We want them spending time on proactive support. We want them reaching out rather than like dealing with customers when stuff goes wrong, we want them reaching out to make sure that everything goes right. That's the future world we want for support.”

“We have a customer service manifesto, which is our set of beliefs about how the world of customer service will change over the next few years. And we've had one before. But before AI, we were mostly about conversational. We pioneered the idea of the chat thing inside your product and on your website. And that was we went hard on conversational.

Today, our manifesto really has four core ideas in it. The first one is bots and humans will work together. That's a very firm belief we have. We believe humans are essential. We want to supercharge humans with AI, and we want AI-powered chatbots to reduce a lot of the work for the humans.

Our second belief is that support should be proactive and reactive, which means that you should be able to get out ahead of problems. Our third is, so all support needs to be conversational and omnichannel. So we talk to customers any way they want to talk to you, anywhere or any way. And then lastly, all of this has to work together. So you can't try and stitch together three or four different tools.

We often save customers from a world where they have a ticketing tool, a docs tool, an outbound tool, a different messaging live chat tool. And they have some Zapier powered or one of those cool integration powered things where they try and stitch it all together and get themselves some source of truth, but it really doesn't work very well. And we do all of that, the higher level thing is in service of an internet full of better customer service. Our mission from 2011 has been make internet business personal, and that's really what we're about.”

Barriers to widespread adoption of AI powered bots for customer support

“The largest barrier is the people aspect. So it's -- customer support, generally speaking, is a human-operated industry. And if we move a button in Intercom's inbox, we get -- our support teams get fed fire by our customers because they're like, oh, if you're going to sneak a single change to this inbox, we have to have an off-site to retrain our entire staff. And when you realize that, that could be hundreds of people, we have customers who have thousands of Intercom seats.

So one single change of, hey, it used to say send and close and now it just says send, that could literally set a large Intercom instance back weeks in terms of support volumes. So we're very delicate about how we make these changes. The other side of that friction is our customers are very, very slow to adopt for a very good reason because they’d say, "Okay, we will try," -- so what we're seeing a lot in say, Fin’s case, we have many, many, many, hundreds, if not thousands of Fin users spitting out tens of thousands of answers on a regular basis, et cetera.

But what we're seeing is everyone wants to dip their toe, they don't want to say, "Let's point Fin at the entire support volume." What they say is, "Hey, let's turn Fin on, on the weekends," or they say things like, "Let's turn Fin on if and only if the question regards resetting a password or something like that." And they are doing that because they want to get a sense of how is it performing in a smaller use case. And then ultimately, we've only really been live to literally everyone, I think about eight weeks.

We have a lot of planned larger migrations where our customer support teams are going to switch over to a massive amount of volume going to Fin, but they're busy working on their knowledge bases and they're busy working on their snippets, et cetera. The snippets being the things that Fin reads to produce answers.

So I think what we're seeing is a lot of people preparing for this world, but the friction is definitely how do I get my support team on board, how do I make sure that we're doing all the right stuff. Even in a lot of cases, all our help docs are out of date and we didn't realize it, but our customer support team were saving our ass. And now we need to get data help docs before we let Fin in.”

Pricing models used for AI in customer support software and considerations when choosing LLMs

GPT-4 when they released it was definitely a head and shoulders above everything else that was out there. So I think we're going to partner with whoever we think is going to give us most access to the best tech. The reason we’d change will be probably more of either somebody else has better tech, which has yet to happen, or it will be like some later day optimization of, hey, you could imagine something like Anthropic is available in an EU instance of Amazon, and we can't get GPT over there. So let's swap or let's -- you can imagine some version like that where we do it for business reasons.

So we’d either -- if we were to go and chase anyone else, it either -- it probably either be like accessibility or availability reasons. It could be tech reasons. We just haven't seen it yet. The last one where I just -- I'd be surprised if it shakes out this way, it's just price. So GPT-4 is expensive. And as a result, Fin is perceived to be expensive. We charge $0.99 a resolution. It's way cheaper than you pay a human, but way more than you'd guess because we get an awful lot of people would just say, "But it's just an API call, how can you charge that much money?"

The reality is that's what OpenAI would charge. So that's the way it -- that's how it checks out that way. But I could imagine if prices continue to run hot and people start to release substantially cheaper versions. There are genuinely features that will be prohibitively expensive for us to build today.

To give you a simple example, summarize every conversation in real time as they happen. We have 500 million, 600 million conversations a month, that would bankrupt is. However, if somebody gave us a substantially cheaper version, all a sudden that's back on the table.

There are pricing implications here. We haven't bumped into them yet and right now, we're still in the innovating and pioneering phase. We're trying to do as much cool stuff as we can. So it doesn't feel like we're yet in the mode to optimize. What I will say, I'm very -- I take a lot of comfort in the fact that there's so many strong competitors here. It tells me that price will go down, availability will go up and the competition to improve the tech will be pretty high.

Trade-offs between AI led resolutions vs human-led

So the first variable is, is your support done by a citizen of the United States working in San Francisco, California, or is it outsourced to an agency and if so, where is that agency located. We've never seen anyone get it substantially cheaper down to those $0.99. There is a nuance to this. If the answer to the question is no, then an agent can do 60 nodes in an hour, and you're probably not paying them $60 an hour, but that's rarely the case.

Most of the time, there's a lot of time taken to onboard agents, train them or get them to be able to deal with the complexity, get them to manage multiple back and forth. But for sure, some people will show me an example and say, "That's definitely not worth $0.99." And that's true. We don't know a priori whether or not the thing that’s worth answering until we answer it.

But in general, we see most support reps paid somewhere between like -- the floor here would be, I don't know, $8, $9, $10 an hour, something like that. We haven't ever outsourced to extreme low-cost providing areas. We've never outsourced support at all. But I'm sure someone will tell me you can get it for $2 or $3 an hour, well, let's see.

But in all these cases, I think most of our customers who are B2B tech companies, generally speaking, they're paying more for their actual support team. And then the other aspect that people often forget is, there's a behavioral difference between a user getting an answer in 0 seconds versus in seven minutes. So if the question was, hey, I've just signed into Asana and I wanted to know how to create a project.

If you answer that question immediately, they go and create the project and they continue to expand and growth goes up. If you answered that question 11 minutes later, they're on a different tab signing up for a different project. So there is value in instant support that goes beyond simply job done.

So, what’s the takeaway from all this? The future of customer support software will still require human involvement, widespread enterprise adoption may take time, reduction in quantity of seats will be offset by higher pricing with an added consumption piece, and companies will need to run the numbers on the trade-offs between costs of human labor and costs of GenAI API calls.

Here’s another quote I thought was worth sharing from Airbnb’s co-founder and CEO Brian Chesky.

“So customer service – the strength of Airbnb is that we're one of a kind. We have 7 million active listings, more than 7 million listings, and every one is unique. And that is really special, but the problem with Airbnb is it's one of a kind and sometimes you don't know what you're going to get.

And so I think that if we can continue to increase reliability, and then if there's something that goes unexpected, if customer service can quickly fix or mediate the issue, then I think there will be a tipping point where many people that don't consider Airbnb and they only stay in hotels, would consider Airbnb.

And to give you a little more color about this customer service before I go to the future, there are so many more types of issues that could arise staying in Airbnb than a hotel. First of all, when you call a hotel, they're usually one property and they're aware of every room. We're in nearly every country in the world. Often a guest or host will call us, and they will even potentially speak a different language than the person on the other side, the host, the guest and host. There are nearly 70 different policies that you could be adjudicating. Many of these are 100 pages long. So imagine a customer service agent trying to quickly deal with an issue with somebody, two people from two different countries, in a neighborhood that the agent may never have even heard of.

What AI can do, and we're using a pilot to GPT-4 is AI can read all of our policies. No human could ever quickly read all those policies. It can read the case history of both guest and host. It could summarize the case issue. And it can even recommend what the ruling should be based on our policies, and it can then run a macro that the customer service agent can basically adopt and amend.

If we get all of this right, it's going to do two things. In the near-term, it's going to actually make customer service a lot more effective because the agents will actually be able to handle a lot more tickets. In many of the tickets, you'll never even have to talk to an agent. But also the service could be more reliable, which will unlock more growth.”

Alphabet’s sum of the parts

From The Information

Alphabet’s biggest “other bet,” part of the blue-sky investment projects carved off from the company’s Google ad-based empire several years ago, is moving toward the exits.

Stephen Gillett, CEO of Verily, an Alphabet subsidiary that aims to apply data analytics to healthcare, told employees this month that by the end of 2024 it would stop using its parent company for a wide range of corporate services, from real estate to software. The move could pave the way for Verily, whose primary business is selling insurance to employers that fund their own health benefit plans but want protection from spikes in payouts, to eventually separate from Alphabet.

Alphabet’s other bets have been contributing to losses for the company for a long time and the market hasn’t really attributed any value to the segment (as the stock trades below a market multiple). Verily has raised at least $3.5bn of capital according to PitchBook and has seemingly struggled to find product-market fit for its data analytics, eventually being applied in insurance products.

Verily, previously called Google Life Sciences, came out of Google’s X incubator and for years worked on numerous bleeding-edge medical projects, such as a pill that could detect cancer and a specialized spoon for people with Parkinson’s disease. But ultimately Verily turned into an insurance business, which now makes up the majority of its revenue. Verily launched the insurance product in 2020 with backing from insurer Swiss Re Corporate Solutions. The plan was to use Verily’s analytics expertise with the insurer’s data and customer relationships to sell stop-loss insurance to employers. That product generated $223 million in revenue in the first half of 2023.

Verily’s revenue rose 94% to $280 million in the first half of 2023 compared to the same period a year earlier, according to a person with direct knowledge of it. That means Verily made up around half of the total revenue Alphabet’s 10 or so other bets generated in the first half of this year.

Spinning off the segment would unlock some value and potentially cash (if it IPOs) for Alphabet and would be a welcomed change in strategy from investors. It should be noted that insurers don’t typically get high multiples in equity markets and Verily generated $540m in operating losses in 2022. This tweet from @wintermoat on Twitter also suggests it might be unlikely that Waymo gets spun-off due to its reliance on Google’s AI technology.

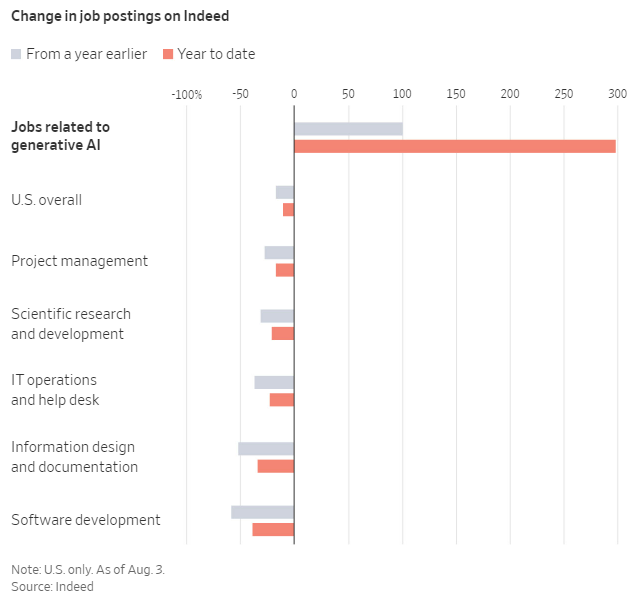

AI engineers are expensive

From The Information

Enterprise software firm Databricks is in early discussions with investors for a new cash infusion, likely totaling hundreds of millions of dollars, as it looks to capitalize on the fervor over artificial intelligence, two people familiar with the matter said.

The investment talks come as Databricks has moved closer to break-even, after losing a total of about $900 million, excluding depreciation and amortization, in its last two fiscal years. That includes a $380 million operating loss in its most recent fiscal year, ending in January, two more people said. The operating loss accompanied revenue growth of more than 70% to over $1 billion in sales, which the company has disclosed publicly.

….

Still, Databricks doesn’t need the cash and might decide not to complete the fundraising, one of the people said. The company has raised $3.5 billion over its 10-year history, according to PitchBook, and has around $2 billion in cash on its balance sheet, according to a person with direct knowledge of its finances. Growing investor interest spurred the talks, another person close to the situation said. Databricks wouldn’t raise new capital at a valuation below its last fundraising price of $38 billion in 2021, the person said.

There are signs its financial performance is improving. While it lost 90 cents for every dollar of revenue in the year to January 2022, the loss narrowed to 35 cents for every dollar of revenue in the year to January 2023. The company expects it will get close to the break-even point by the end of this fiscal year, one of the people said.

The figures out of this are pretty astounding, reflecting the crazy funding environment that currently pervades the AI industry. I don’t blame the company for trying to capitalise on it though. If recent history has taught companies anything, it's that they should seize the opportunity to raise funds when capital markets are favorable and money is readily available—even if the funds aren't immediately needed. This principle aligns with one of the maxims of George Doriot, the founder of modern venture capital. For Databricks, the majority of expenses are tied to the salaries of engineers and salespeople, and if this report from the WSJ is anything to go by, top talent in AI isn’t cheap.

Recruiters say they see pay edging up because the available supply of AI practitioners is falling short of demand, particularly for midlevel and higher-level positions.

“This is pure market economics,” said Paul J. Groce, a partner and head of the Americas at the executive recruiting firm Leathwaite, where for years he has worked on searches for high-level technology talent. “We do not magically have thousands of additional AI developers, product managers and everything else.”

Salaries for AI roles vary based on the experience required and the company hiring. Total compensation, which typically includes bonuses and stock-based grants, can push overall pay much higher. A product manager position for a machine-learning platform at Netflix lists a total compensation of up to $900,000 annually. The posting for that job gained attention on social media last month amid the strike of Hollywood actors and writers.

Related: Microsoft plans AI service with Databricks that could hurt OpenAI

Misalignment of investment time horizons

This week saw two significant earnings surprises that caught my attention, appearing quite similar at first glance: Sea Limited, the Southeast Asian internet conglomerate and Adyen, the Dutch payments acquirer. Both companies saw their share prices plummet by over 25% following the release of their earnings reports and subsequent conference calls. I believe the root of this sharp decline lies in a divergence between the investment time horizons of the companies' investors (which is typically 12-18 months) and their management teams. Allow me to explain.

From Forbes

Sea’s shares suffered their biggest daily drop since the company went public in 2017 on Tuesday, when they dived almost 29% on the New York Stock Exchange. The stock plunge erased roughly $1 billion of chairman and CEO Forrest Li’s fortunes, bringing his net worth to $2.5 billion on Forbes’ Real-Time Billionaires List. Meanwhile, chief operating officer Gang Ye lost around $565 million from the shares decline, leaving his net worth at $1.8 billion.

Sea said on Tuesday that its second quarter revenue recorded a 5.2% year-over-year increase to $3.1 billion, falling short of the $3.2 billion that analysts have estimated. Its e-commerce business Shopee, which contributes about two-thirds of the company’s top-line, posted its slowest growth rate at 20.6% to $2.1 billion. Revenue at its profit-making gaming unit, which helped fund Sea’s expansion in e-commerce and digital financial services, plummeted 41.2% to $529 million, while sales from digital financial services rose 53.4% to $423 million.

Sea said it collected a net profit of $331 million in the second quarter, compared to a loss of $931 million in the same period last year. The company, however, signaled that it may once again bleed red ink. “We have started, and will continue, to ramp up our investments in growing the e-commerce business across our markets,” Li said in an earnings call. “Such investments will have impact on our bottom-line and may result in losses for Shopee and our group as a whole in certain periods.”

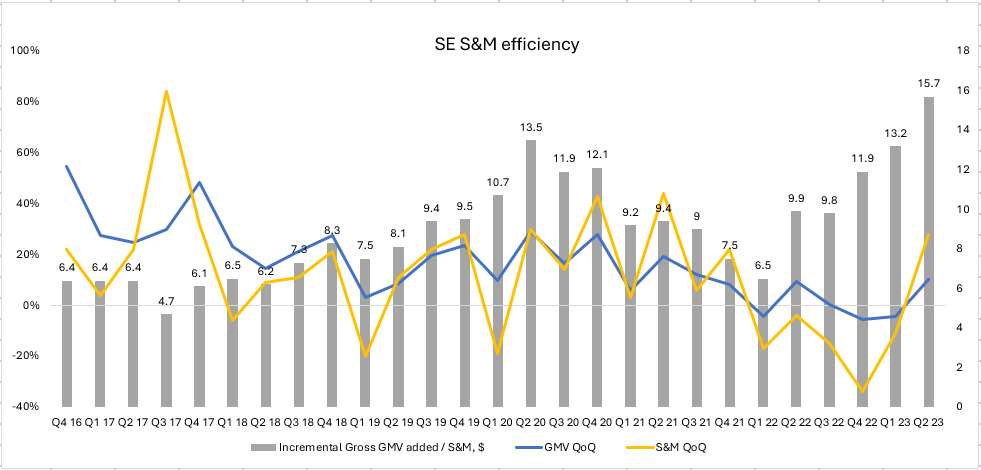

Over twelve months ago, upon advice from investors and sensing an overall shift in the market’s appetite for cash burning companies, Sea pivoted its strategy (within its core ecommerce business, Shopee) from growth at all costs to profit above anything else. It wanted to show to the market that it was self-sufficient and didn’t need to return to the capital markets to grow and operate the business. This led to EBITDA in Ecommerce swinging from $648m in losses in Q2 22 to $208m in profits by Q1 23. It involved intense focus on cutting costs such as exiting unprofitable markets, reducing S&M spend and shipping subsidies to get rid of low-quality orders and customers from the platform. Of course, this meant that GMV growth would inevitably slowdown from +27% yoy in Q2 22 to an estimated -1% yoy in Q1 232. So, what happened at the Q2 results that caused the stock price to tank 28%? I believe it come from a mismatch in time horizons. Investors had expected the company to continue to show improving profitability and accepted the fact that GMV growth would slow and possibly decline this year as the company resets its business (consensus estimates for FY23 GMV at the start of May were to be slightly down - flat). Instead, the company shared that it sees resilience in its regional economies and is confident that now is the time to start ramping up investments to grow its ecommerce business across its markets. Some investors were caught off guard, not knowing the company had started to switch its mentality a few months ago, selling the stock as it “lacked” valuation support (to be fair, the company also said investments will have an impact on the bottom-line and may result in losses for Shopee and potentially the group as a whole in certain periods, which didn’t help instill confidence). Investors had come to value the company on near-term earnings (it traded at 22x NTM PE pre-results), while management commentary suggested this could go negative as they were choosing not to optimize for higher near-term profits. Therein lies the mismatch.

Southeast Asia as a region has excellent demographics for GDP growth and low penetration rates for ecommerce. You can comfortably underwrite mid-teens growth in ecommerce over the next decade3. Meanwhile, the region is home to a number of multinational competitors all vying for the same opportunity. According to Momentum Works, Shopee had almost half of the ecommerce market in 2022, while Lazada (owned by Alibaba) came second with ~20% share. Lazada used to be the biggest player (originally founded in 2012) but was overtaken by Shopee (started by Sea in 2015) just a couple years ago. Up until Q4 22, no major player made money in ecommerce in Southeast Asia. The environment was rife with aggressive promotions and marketing spend. When market conditions shifted in late 2021, so did all the major players. They all started to rationalise in search for profits. Now that Shopee has reached profitability, the management team believes that now is the time to push and defend/grow their share (and improve customer experience by investing in logistics) while their competitors are still trying to get to profitability. The path isn’t all crystal clear though, another formidable competitor has also recently popped up - TikTok Shops. I’ve written about TikTok’s ecommerce ambitions in last week’s post, but it’s been gaining share in the region, aggressively signing up merchants with friendly commission terms and offering consumers generous promotions. Part of this pivot from Sea is to not over-earn in a region that’s ripe with long-term growth potential and cede further share to a strong global competitor that could potentially become a bigger threat to its business. I think this shift makes sense, taking short-term pain in profits to extend durability and duration (and note that none of its competitors generate a profit in the region). This playbook has been used before by Costco and Amazon, and as much it is an investing cliche (and maybe cringe-inducing), I really do think scaled-economies shared is a powerful business model. We also need to take into account the $4bn in net cash it has on the balance sheet (making up 19% of its market cap) - management aren’t getting any credit for it in their valuation, so they can either spend it (hopefully wisely) on high ROIC projects internally or buy back shares. Given the stage that the business is at, I would prefer them to fund growth (as long as the unit economics make sense).

The push-back I’ve gotten is that this pivot proves the company can’t grow without growing S&M, or that S&M spend is going to incredibly inefficient going forward (and this is basically implied as much in consensus forecasts). Q2 23 S&M spend grew 28% QoQ and by my estimates GMV grew only 10% QoQ (and was flat YoY). The QoQ movements aren’t dissimilar to previous second quarter seasonality (ex 2022) and we have to remember that Q2 22 was the period that the company started to shift away from unprofitable orders, creating a tougher comp in 2023. Consensus GMV estimates for 2023 and 2024 were taken up 0.39% ($290m) and 0.63% ($506m) while S&M estimates for 2023 and 2024 were taken up 15% ($315m) and 23% ($522m). This implies that for every extra $1 the company is spending on S&M, it will get <$1 in GMV. This doesn’t reconcile with the company’s historical S&M efficiency.

Now this calculation doesn’t capture its logistics subsidies that get netted off in its 3P marketplace take-rate, but even when taking this into account, its efficiency is still nowhere near as low as implied. You could argue that the company needs to subsidize shipping in order to generate growth, and that’s true to an extent. The category is still nascent, and as such, Shopee must reduce friction in the ordering process to attract more consistent buyers. By enhancing the ease of purchase and increasing order frequency, they can foster loyalty and encourage repeat purchases. I expect these subsidies to level off over time. Still, it looks like the company is not getting any credit for this extra spending (implied by GMV forecasts) so I strongly believe long-term investors will be rewarded from being patient here.

Some quick back of the envelope math on valuation: If we assign $7.2bn to its gaming business (assuming it generates $900m EBITDA in perpetuity) and take into account its $4.1bn in net cash on the balance sheet, that leaves an implied $10.7bn in value for its ecommerce and digital financial services (DFS) business. DFS is run rating ~$550m in EBITDA and grew revenue 53% yoy in Q2, while the ecommerce business generated 1.2% of its GMV in EBITDA in Q1 before it dropped to 0.8% in the latest quarter. If we conservatively apply 1.2% as a ‘steady state’ EBITDA margin to consensus estimates for 2023 GMV we get $890m in ecommerce EBITDA, which implies the market is valuing its ecommerce and DFS business at 7.4x EBITDA. Its Latin American peer MercadoLibre with a similar ecommerce and fintech business trades for 30.7x EBITDA. Sure, a discount is probably deserved but 75% seems far too big.

A similar story came out of Adyen’s results this week. From Reuters

Dutch payments processor Adyen NV's (ADYEN.AS) shares fell by a third on Thursday, wiping more than 13 billion euros off its market value, after first-half earnings missed estimates, as sales growth slowed and hiring costs hit margins.

Analysts said the company's performance raised concerns about stretched valuations in the digital payments sector and added to worries about a general slowdown in what has been viewed as a high-growth business.

The company’s initial valuation was quite distinct, trading at 58x NTM PE prior to the decline. However, its strategy choices and subsequent reaction in share price highlighted a similar divergence between the investment horizons of the management team and its investors. At a time in 2021 when there was a war for tech talent across the industry, Adyen chose to be measured about bringing more people on. From its H2 2021 shareholder letter.

When it comes to building Adyen for the long term, it’s not just about market shifts and merchant needs. Operationally, it’s essential that we identify bottlenecks for future growth in order to sustain and accelerate from our current pace. One of these potential bottlenecks is in the hiring of talent. Macro conditions (e.g. the war on talent) and a refusal to lower the bar for new hires in order to achieve scale in the form of quick additions has resulted in a growth of 226 FTE during the period. We don’t believe it’s in our interest to mortgage the long-term for short-term gains in FTE count.

That said, all things being equal, we would have liked to hire more during the period. Accordingly, we’ve invested in our recruitment infrastructure and in two new tech hubs to help ramp up hiring during 2022. These tech hubs – one in Chicago and one in Madrid – should provide us with increased global coverage and scale as we build out a technical organization that has historically operated primarily out of Amsterdam. On December 31, 2021, the Adyen team totaled 2,180 FTE.

Now, while the rest of tech industry has been laying off staff, Adyen is seizing the moment as a golden opportunity to acquire top talent at a more affordable price. From its H1 2023 letter.

Beyond the current industry dynamics in North America, another factor that impacted our growth was one we wrote about at the end of 2021 too: the fact that we would have liked to grow our team at a higher pace but were unable to hire enough top-quality talent. We now see the impact of a sales team size that did not match our ambitions, particularly in North America. Since then, we have ramped up our investments. That being said, investments in the team and revenue never move simultaneously. Rather, the former drives the latter over time. …. To continue in this stead but at even larger scale, H1 was a key investment period to grow the team to its next level of maturity. We added 551 colleagues during the first half of the year, bringing the Adyen team to a total of 3,883 FTE. Of our new joiners, a majority (75%) sat in tech roles developing both young and more mature initiatives that power our global customer base. Our team and culture have always been central to realizing our success and remain the primary means of investing in our future. We foresee our team reaching its next level of maturity at the start of 2024 with a mix of both commercial and tech roles. After this point, we will phase out of our accelerated investment mode and hire as needed.

Primarily driven by our investments in the team, EBITDA margin was 43% in H1. We could have actively optimized this metric, but prefer building the team that can realize the long-term potential of our single platform. With increasingly positive interest rates as a tailwind to our interest income, we were able to invest in the business while keeping our bottom line solid. We have always maintained a strong balance sheet to enable rapid and flexible execution. An essential part of our competitive advantage is the efficiency of our single code base. To allow for this efficiency at even larger scale, we front-loaded this year’s priority infrastructure investments. This resulted in CapEx of 7.6% for H1, which is expected to be at 5% for the full year.

This increased investment is also coming at a time where the company is seeing more competition on price in the US.

First, as a natural consequence of the shifting economic climate – driven by higher inflation and interest rates – profit outweighed growth for many North American digital businesses in H1. Enterprise businesses prioritized cost optimization, while competition for digital volumes in the region provided savings over functionality. These dynamics are not new, and online volumes are easiest to transition back and forth. Amid these developments, we consciously continued to price for the value we bring.

I thought this twitter thread by @BankBraavos explained the situation well.

The management team is reluctant to engage in a price war, recognizing that it could undermine the industry's long-term economics. They understand that once prices are reduced, reversing the decision can be a challenging endeavor, potentially leading to lasting negative consequences. It’s possible that the management team think aggressive price moves from Braintree are temporary to drive adoption in PayPal’s cash cow - the core button. Industry participants are well aware of how poor the Braintree product is, generally slower with terrible reporting and lower authentication rates. Nevertheless, it’s hard to say no to when businesses are prioritizing cost optimization and the product is being offered for 4x less4. At some point though, Braintree needs to be able to operate profitably as a standalone business. It may be a rocky period for Adyen, but not engaging in this price war for digital businesses will benefit the company in the long run, and taking a short-term profit hit due to investment in extra sales capacity will help to reaccelerate revenue growth. It already has a leading cost position in the industry (43% EBITDA margins in H1 23, and 59% the year before), so regardless, it’s in a better position than most to withstand a significant price war (Stripe is still loss-making and Credit Suisse estimate Braintree’s gross margins at 25%).

That’s all for this week. If you’ve made it this far, thanks for reading. If you’ve enjoyed this newsletter, consider subscribing or sharing with a friend.

I welcome any thoughts or feedback, feel free to shoot me an email at portseacapital@gmail.com. None of this is investment advice, do your own due diligence.

Tickers: MSFT 0.00%↑, CRM 0.00%↑ , NOW 0.00%↑, ABNB 0.00%↑, GOOG 0.00%↑, SE 0.00%↑, $ADYEN, BABA 0.00%↑, PYPL 0.00%↑

Side note: ChatGPT plus is charging $20/month/user while capping messages at 50 every 3 hours for its GPT-4 model.

The company stopped reporting GMV in Q1 23 as they wanted investors to stop focusing on growth while they get to profitability.

According to various industry reports floating around the internet

According to an expert transcript from Tegus